Human-centered design (HCD) is a framework for building products based on the needs of people, rather than requirements.

It originated in the private sector but is now gaining broad adoption among government agencies. For example, many organizations are now developing their own in-house HCD teams, while others are requiring vendors to demonstrate that they can effectively apply human-centered methods. All of this is good news for the millions of people that rely on government digital services.

However, while HCD is gaining traction, its underlying concepts are still new and sometimes misunderstood. Even among experienced practitioners, there is a lack of consensus on what HCD is, how it works, and what success looks like. This can mislead teams into thinking they’re working in a human-centered way when in fact, their work is largely driven by requirements.

Below are four common myths to consider when building your own HCD practice or when partnering with vendors that say they provide HCD services:

Myth #1: HCD is just about UI/UX

HCD is made up of many different approaches and techniques aimed at building the right things based on people’s needs.

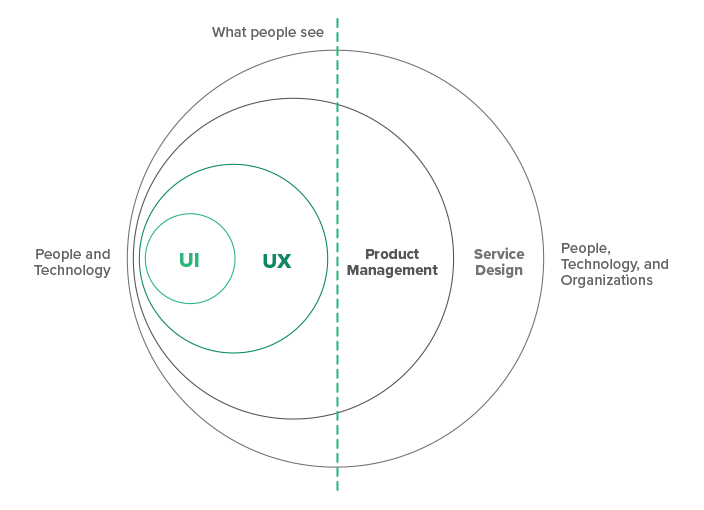

User interface and user experience (UI/UX) are specific aspects of design that play an important role in HCD, but typically focus on user needs from a visual or experience perspective, rather than in terms of enabling a service as a whole. This distinction is important because an effective digital service works for everyone involved — from the users of a new digital application to the back office staff that support it. It’s also why we emphasize “human” and why we use the term “human-centered design” instead of “user-centered design.”

Also, in order to deliver a service that meets people’s needs, we need to consider factors that go “beyond the screen,” like how new digital touchpoints should interact with the people, process, and technology that support it. All of this requires a broader view than just UI/UX design and a variety of tools, techniques, and perspectives so that we can deliver effective services that meet given goals, needs, and constraints.

Myth #2: You don’t need a cross-functional team to practice HCD

Since HCD is focused on more than the user experience, it works best when supported by a cross-functional team that includes product management, engineering, research, and design. These teams work together from start to finish to explore problems from a variety of vantage points, rather than in siloed research, design, and engineering phases.

In a cross-functional setting, engineers participate in user research and designers work with engineers to evolve ideas from simple mockups to working code. Similarly, product managers and researchers play important roles in the design process by helping teams set focus and incorporate feedback that informs product direction.

This way of working is ideal for modern digital service delivery because HCD is about discovering what works best for people, rather than working linearly towards a predefined solution. As a result, cross-functional teams work iteratively, rather than incrementally, and are equipped with a variety of skills and perspectives that allow for the best ideas to emerge more quickly and with greater confidence.

Finally, cross-functional teams are important because it’s everyone’s job on a digital service team to ensure they’re meeting the needs of the people they serve. In other words, HCD is a collective responsibility, and adding a designer or two to your project doesn’t necessarily make it human-centered. An effective HCD practice needs to be supported by a variety of disciplines and a way of working that promotes collaboration and learning so that teams can deliver solutions that are not only desirable but also feasible and viable at scale.

Myth #3: Learning only happens at the start and end of a project

A common trap that many digital service projects fall into is that learning from users only happens at the start or end of a project. This can either take the form of an initial “discovery” phase that defines requirements for the team to execute against or as user acceptance testing that happens just before a product is released to the public.

While any kind of engagement with users is better than none, user feedback should be incorporated throughout the product development process. At Ad Hoc we call this “continuous discovery,” and it’s key to how we work and facilitate decision-making with customers. This is because a single discovery phase only provides a snapshot of our understanding of people’s needs, some of which may change over time.

There are also limits to what a team can learn from user research alone. Sometimes the most important insights emerge only after we put new ideas in front of people and observe how they interact with them. As a result, organizations should understand the difference between user research and user testing, and empower teams to use both to guide delivery.

Myth #4: You can start practicing HCD without making significant changes to how your team works

The fourth and perhaps most important misconception about HCD is that you can practice it effectively without making significant changes to how your organization and its digital service teams work. Above all, human-centered design requires teams to have the flexibility to discover solutions, rather than just work towards requirements. This requires a willingness to test ideas early and often, and incorporate what you learned from users to inform decision-making, even if this means it takes you in a direction you didn’t expect. Finally, HCD redefines success in terms of enabling outcomes for people, rather than measuring output, like the number of story points completed in a sprint.

HCD is about putting the needs of people, rather than requirements, at the center of your process. It also requires the courage and capacity to discover solutions with the people you’re solving for, rather than managing against a plan. For many organizations, this will require significant organizational and cultural change, but they are necessary evolutions for meeting the public’s rising expectations of a 21st-century government.